THE HIDDEN GALLEON

Assateague Island

On the lonely sand beaches of Assateague Island, there is a herd of wild horses that legend says arrived by way of a Spanish galleon wrecked in the 18th century. There was such a galleon which lies buried within the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. This secret is closely guarded by government bureaucrats. They also consider themselves to be the guardians of the horses origins. They do not want the public to consider that the horses came from a Spanish galleon while at the same time they are blocking archaeological investigations of the known location of the legendary Spanish galleon. Now, that cat is out of the bag. Scientists have recently unearthed a horse molar from a 16th century Spanish settlement on Hispaniola whose DNA most closely matches the DNA of the Assateague horses. Read on.

In 1946, children’s author, Marguerite Henry, was drawn by this curious and pervasive legend to travel to

Misty of Chincoteague

Chincoteague Island, Virginia, to witness the wild ponies for herself. She heard first hand from the Beebe family and others about the long-held belief that the Assateague horses that had have run wild for centuries descended from those that swam ashore from the shipwreck of a Spanish vessel. Of course, no one could remember the ship’s name or when she had wrecked, but the horses that Mrs. Henry had so longed to see came from La Galga, a Spanish warship that drove ashore on Assateague Island on September 5, 1750.

La Galga had departed Havana, Cuba, on August 18, 1750, escorting six other merchant ships carrying treasure back to Spain. On August 25, the fleet encountered a hurricane off of northern Florida and was driven farther north by wind and currents to wreck along the coast of North Carolina and Virginia. Fortunately, two of the ships made it safely into Norfolk, Virginia.

La Galga sat in the surf while the Spanish crew made their way ashore on a raft which was tethered to another wreck on the beach. Unfortunately, the raft overturned on one trip spilling two chests of treasure into the surf where they settled irretrievable and out of sight. After three days, the Spaniards were shuttled to the mainland by the locals who then set to work salvaging the shipwreck. Even though La Galga later broke up, her location was not forgotten by some of the inhabitants who not only remembered her location but that she had brought the horses to Assateague. Today, they still have detectable Spanish blood in them.

In 1947, Marguerite Henry published Misty of Chincoteague, winning her honors, and her book has sold millions and is even required reading in some grade schools today. In 1961, her story was made into a movie. Every year nearly 50,000 people come to Chincoteague to witness the annual pony swim and auction. The Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge and the Assateague National Seashore host nearly three million visitors a year. Many are drawn by the horses.

The Archives of Maryland

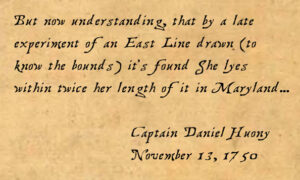

In March of 1978, I made the fateful discovery of the clue to La Galga’s location. It was the letter written by Captain Don Daniel Huony of La Galga to the Governor of Maryland in November 1750. Huony gave an account of his running ashore on Assateague and that he was forced to abandon his ship in the surf.

The Captain’s Clue

The locals set upon her looking for treasure. A dispute arose over which jurisdiction the ship lay in. Captain Huony was told after coming ashore that La Galga lay in Virginia. The Spaniards remained on Assateague for three days before traveling to Snow Hill, Maryland, and then to Norfolk, Virginia, to gain passage back to Spain. Before Huony left for Spain, the authorities conducted a survey to situate the shipwreck. Huony then reported the results to the Maryland Governor, Samuel Ogle: “Now understanding by a late experiment of an East Line drawn (to know the bounds) it’s found She lies within twice her length of it in Maryland.”

I was convinced that La Galga could be easily found and immediately began preparations to search for her. I knew that the 1750 boundary would have to be different than it is today. Hence, additional research suggested that the old line lay at approximately latitude 38 degrees or nearly two miles south of the present boundary. The range of search would be no more than two miles. The ship sat in shallow water after running aground, so it had to be within several hundred yards of the beach. A boat towing a magnetometer at five miles per hour could cover the two miles 250 yards out with fifty-foot separation of the transects in approximately six hours. This sounded extremely easy. I had not heard or read about La Galga’s previous discovery. If it was this easy, why hadn’t somebody already found it? Research in the Spanish archives produced the ship’s manifest, which said that La Galga was not a “treasure ship.” But the manifest did describe a small chest containing gold doubloons that belonged to a priest. A contemporary newspaper account described two chests washing off a raft between the wreck and the beach. These chests appeared to have been unregistered.

The Hunt for La Galga

In April 1980, the very weekend that my partner and I made our first trip to Chincoteague, I was made aware that I had competition from a man named Donald Stewart and his treasure hunting company, SEA, Ltd.

Donald Stewart behind the USS Constellation

Assateague Island Visitors Center 1982

Stewart’s San Lorenzo hoax

What I didn’t know at the time was that he was a con man. He had already defrauded the City of Baltimore, the State of Maryland, and the Federal Government into believing that the USS Constellation docked in Baltimore Harbor was the original built in Baltimore in 1797 when it was actually built in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1854. Stewart also wrote an elaborate hoax about a make-believe ship called the San Lorenzo, which supposedly wrecked in 1820 on the beach of present-day Ocean City, Maryland. Stewart described the San Lorenzo as carrying tons of gold and silver and a small herd of blind mine ponies that were the forefathers of the wild horses on Assateague today. The National Park Service was seduced by this story and erected a wayside exhibit at the visitors’ center on Assateague and published his story in the official Assateague Island handbook.

The summer of 1980 ended with no success in locating La Galga, but we had discovered magnetic debris about 600 yards south of the Maryland-Virginia border. I had been drawn to this northern area because Stewart had claimed to have found Spanish artifacts on the beach here. Since I had failed to locate the shipwreck and had no longer had a partner, I contacted Stewart by phone and told him what I knew and where I had located magnetic anomalies. We met days later to discuss La Galga. He seduced me with his San Lorenzo story and said he had documents related to La Galga from the Spanish archives that he had locked up. Stewart showed me what appeared to be an old 18th century chart of the area, which had a wreck symbol in the exact area where I had discovered magnetic anomalies. At the time, I didn’t know that he created it immediately after our phone call in preparation for our meeting.

I bought into SEA, Ltd. and Stewart’s fraud joining thirty other suckers as investors. I quit my comfortable job in Washington, DC, and went to work for SEA, Ltd., which gave me a front-row seat to what was about to take place.

We thoroughly surveyed the area close to the beach and found more magnetic debris, but while it was from a wreck, we determined that it could not be La Galga. Stewart then directed SEA, Ltd.’s searches to four make-believe shipwrecks: The San Lorenzo, the Santa Clara, the Santa Rosalea, and the Royal George. All of these wrecks Stewart claimed to have documented wrecking along the beaches of Ocean City, Maryland.

My suspicions began to grow as nothing was located at Ocean City. I contacted my researcher in Spain to investigate the San Lorenzo and the Santa Rosalea. She reported back that she found nothing on the San Lorenzo but did find that the “Santa Rosalea” was spelled Santa Rosalia and it was a real ship that did not wreck in 1785 as Stewart had claimed. It hadn’t wrecked at all. By the fall of 1981, I knew then it was time to go after Stewart. I quit SEA, Ltd. and began building my case against him. Stewart was sued and later settled out of court. He died in 1996, but his frauds did not. His make-believe San Lorenzo story continued to circulate.

St. Rosalia

It was the “Santa Rosalea” that I disproved first, followed by the others. During this process, I would find that Saint Rosalia would reveal herself to be the patron saint of mariners.

On her feast day, September 4, 1750, La Galga was spared certain destruction on a reef miles from Assateague. She struck twenty-five times before sliding into deeper water. She was only held together by the twisted ropes drawn between her sides . The next day she drove ashore. No lives were lost, and the horses were saved. However, five drowned trying to swim ashore rather than remain with the others. Had La Galga perished on September 4, I would not be here today writing about this.

In 1982, a new group was formed by myself and four other SEA, Ltd. investors and a Virginia Beach attorney named Albert Alberi. Our goal was to survey the area around latitude thirty-eight degrees which research suggested was the old colonial boundary. We had no luck.

I went to the Accomack County courthouse and searched old land records where I found a plat dated 1943 prepared for the federal government’s takeover of the Virginia portion of Assateague. The plat not only documented the oldest boundary lines between Maryland and Virginia but demonstrated that the beach had built out over the centuries. This explained why we could not find La Galga. It was buried beneath Assateague. But it also told us something else. La Galga and the legendary Spanish shipwreck that brought the horses to Assateague were one and the same. The documented legend says that this Spanish ship had been swallowed up in a forgotten inlet.

The Spaniards leave clues

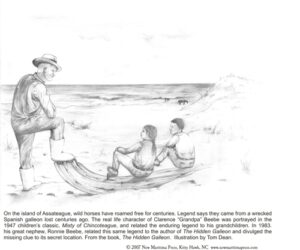

Because of the historical significance of La Galga that we now understood, we decided to continue our search  on land with a portable magnetometer. Our land search began in early 1983 in the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. Before the magnetometer arrived, I had interviewed some locals of Chincoteague. I found that there had been a former inlet and was told about timbers sticking up out the marsh said to be remains of the Spanish ship seen in the early 1900s. I was also told about a Spanish pistol and some Spanish coins found in the woods nearby, and the old inlet was pointed out as where the Spanish ship wrecked that brought the ponies to Assateague. The man’s name was Ronnie Beebe, the grandnephew of Clarence “Grandpa” Beebe immortalized in Misty of Chincoteague. We now realized that the legend was provable fact.

on land with a portable magnetometer. Our land search began in early 1983 in the Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. Before the magnetometer arrived, I had interviewed some locals of Chincoteague. I found that there had been a former inlet and was told about timbers sticking up out the marsh said to be remains of the Spanish ship seen in the early 1900s. I was also told about a Spanish pistol and some Spanish coins found in the woods nearby, and the old inlet was pointed out as where the Spanish ship wrecked that brought the ponies to Assateague. The man’s name was Ronnie Beebe, the grandnephew of Clarence “Grandpa” Beebe immortalized in Misty of Chincoteague. We now realized that the legend was provable fact.

Aerial photographs and old maps, plats, and charts further proved that there was an old inlet. Since we knew La Galga was not in the ocean, we anticipated success on land. After we located a magnetic anomaly we were convinced by a preponderance of the available evidence La Galga was buried within the Refuge. I prepared a research report and submitted it to federal authorities thinking they would be excited to know that this significant historical treasure was buried on their land. I used their own documents to make the case. To my surprise they only noted it in their records. NOAA, however, published the information in their shipwreck database which is available to the public.

Sea Hunt Inc.

In 1998, a treasure hunting company called Sea Hunt, Inc. was formed by Ben Benson who thought he could locate La Galga in the ocean. He had read my research report from 1983, which documented the all-important boundary line but he concluded that I must be wrong because the federal government had failed to act on my research report. So he ignored the documented boundary and declared the boundary could be anywhere. He was directed to the location formerly worked by SEA, Ltd. and was led to believe that the magnetic debris field we mapped in 1981 was La Galga. Had he taken the time to verify my findings in 1983, he would have realized that this debris field could not have been La Galga. Subsequent research on my part suggests that the debris field is from the American bark, Sunbeam, wrecked in 1852 at this exact spot. It had sailed from Havana, so it most likely had some Spanish money on board. Spanish coins had been found on the beach opposite this spot and were part of the inspiration for Stewart’s fraud. Neither Stewart nor Benson knew that Spanish coins were legal tender in this country until 1857. Therefore, any shipwreck could be carrying such coins.

In March of 1998, Sea Hunt filed claims in federal court in Norfolk, Virginia, to La Galga and another Spanish ship called the Juno, which the Spanish archives document sank hundreds of miles off Assateague in 1802. Benson, like Donald Stewart, was seduced by Spanish coins found on the beach, believed that the Juno lay just off the southern end of Assateague.

“It would amaze and surprise most citizens of this country, when their dream, at the greatest of costs, was realized, that agents of respective governments would, on the most flimsy of grounds, lay claim to the treasure.”—Judge William O. Mehrtens, 1978 Treasure Salvors case

The Department of Justice contacted Spain and informed them that if they filed a claim for these shipwrecks in the Sea Hunt litigation, they would represent them at U.S. taxpayer expense. The Departmeny of Justice and the Kingdom of Spain invoked their Treaty of Friendship of 1902 that would give Spain prtotection in U.S. waters. The Court ultimately disallowed the representation by the DOJ, so Spain hired their own attorney. But the DOJ continued to file friend of the court briefs acting as CHEERLEADERS for Spain. The DOJ saw a chance to win a treasure case finally and gain a precedent to be used against future treasure hunters. Spain was not told of my findings made in 1983. In 1982, they had lost in the Supreme Court to Treasure Salvors, Inc. over the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, one of the richest Spanish galleons ever found. The case began in 1978 and ended with the District Judge’s opinion scolding the governments’ lawyers: “It would amaze and surprise most citizens of this country, when their dream, at the greatest of costs, was realized, that agents of respective governments would, on the most flimsy of grounds, lay claim to the treasure.”

In Sea Hunt, the only evidence given to the Court that two Spanish shipwrecks had been found was Benson’s intangible “information and belief.” Some artifacts were found at an unidentified wreck nine miles south of what Sea Hunt believed was La Galga, but no one could identify them as coming from these two wrecks, not even Spain or the National Park Service. Although hesitant to conclude that the Spanish shipwrecks had been found, the Court awarded them to Spain anyway since all of the parties agreed that they had to be somewhere in the ocean just off Assateague. But that conclusion is easily proven wrong. In post judgment proceedings, the Commonwealth of Virginia declared in court; “No court has ruled that La Galga and the Juno have in fact been found or that their remains lay within the two search areas.” It seemed that Spain’s court victory was a foregone conclusion as they ignored the facts that unfolded in court.

There was a lot of doubt about Spain’s victory since no evidence of discovery had come to light. In the hopes of erasing that doubt, the Department of Interior, the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the State of Maryland sent a nautical archaeologist out to find these wrecks. Unfortunately, the report came back documenting that La Galga could not be found and that the wreck believed to be the Juno was not the Juno.

Newly discovered evidence proves that the Juno sank in international waters. The Treaty of 1902 only covers Spanish ships lying within twelve miles of the coast therefore there would be no blanket protection for these shipwrecks under this Treaty.

In 1802, a Charleston newspaper transposed the longitude from 67º to 76º misleading Spanish officials in Havana, Cuba, when the dreadful news was forwarded to Spain. Since La Galga lies buried under Assateague Island and Juno lies over two hundred miles off the coast, the 1902 Treaty does not apply. And since neither shipwreck was properly arrested, Spain had no standing to be in the case. The judgment rendered in Sea Hunt is merely an Advisory opinion. Advisory opinions are prohibited under Article III Section 2 of the Constitution.

The Hidden Galleon exposed

In 2007, I published The Hidden Galleon documenting the history of La Galga and my search for her, the con man, SEA, Ltd., and an inside look at the Sea Hunt litigation. Months later, I hired archaeologists to go to Assateague to survey the area believed to contain the wreck. After I filed for the permit to conduct remote sensing without any digging, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service contacted the Spanish Embassy and had them issue a letter recommending that no archaeological verifications were to take place. The USFWS held firm for six years, and then for some inexplicable reason, they permitted us, without interference from the Spanish Embassy, to conduct remote sensing with a magnetometer but still would not allow ground disturbance necessary for verification. Three days of fieldwork between 2014 and 2018 resulted in locating a debris trail from the wreck, which proved that the all-important Maryland-Virginia line of 1750 was not latitude 38 degrees but the line drawn in 1687 for the original patents of land. The federal government documented the approximate position of this line in 1943 and it was well south of the Sea Hunt wreck.

In 2010, in another bid to convince the public that La Galga had been found by Sea Hunt, the National Park Service and the Kingdom of Spain jointly contrived an exhibit of a few of the Sea Hunt artifacts to be put on display at the Assateague Island National Seashore Visitors Center. The few Spanish coins that were found were displayed. These coins and other artifacts had been recovered nine miles from what Sea Hunt claimed was La Galga. No wonder they are blocking verification of the site on land within the wildlife refuge.

Find the Boundary Line and you’ve found the wreck

Captain Huony reported in 1750 the final determination of the Maryland-Virginia boundary line placed his ship just north of the Maryland border. The survey was done to establish who had jurisdiction over his ship. However, when he first arrived at Assateague, he was told he was in Virginia. In the Spanish archives, it is also recorded that he was told he was at the border in Virginia. These testimonies do not conflict; they merely document there were two determinations of that boundary, and they were very close together.

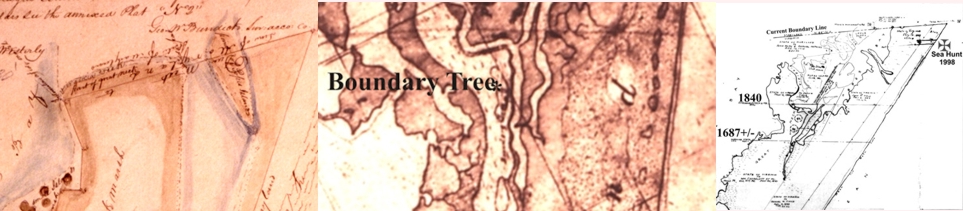

LEFT: 1840 boundary-Accomack County Courthouse; MIDDLE: 1859 Survey-National Archives; 1943 survey-Accomack County Courthouse. Note on 1943 position of Sea Hunt wreck. Not even close.

In my report to the government in 1983, I provided proof of these two lines. A survey was done in 1840 documenting a patent for land that bordered the Maryland-Virginia boundary line. Research suggests that this line had been official going back to the 18th century. I also included in my report, the plat from 1943 prepared for the Department of Interior that gave the history of land patents going back to 1687 when Maryland and Virginia issued their first patents for Assateague. Unfortunately, the surveyor and preparer of the 1943 survey report was not exactly sure where the 1687 boundary was, so he drew it with a +/- alongside. This was easily cleared up with another federal survey done in 1859 by the Coast and Geodetic Survey, which recorded a “Boundary Tree” near the island’s west side. A line drawn east from here passes just below the “Point of Pope Island” indicated on the 1840 plat. This point was described in Maryland’s 1687 patent, it being the southern point of Maryland’s patent. This line extended eastward passes through the former inlet disclosed to me by Ronnie Beebe in 1983. The distance between the two lines is approximately 200 yards. Therefore, La Galga has to be lying within these two lines.

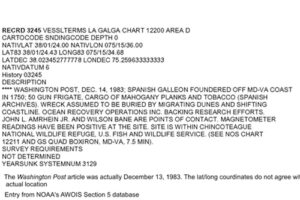

Former Entry in NOAA’s shipwreck database first recorded in 1984. This was available to Sea Hunt, and the Department of Interior when the salvage claim was filed in 1998

In December of 1983, a full research report was prepared and submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of Interior, National Geographic, the Smithsonian Institution, and the press. NOAA picked up on it and recorded the discovery in its AWOIS shipwreck database. Unfortunately, the Department of Interior refused to do any follow-up. Had the federal government heeded this information I provided to them in 1983, there would have been no Sea Hunt case, and the shipwreck would be proudly on display in a museum today, just as the steamboat Bertrand discovered in the Desoto National Wildlife Refuge. I offered to help the government pinpoint the wreck in 1984, but they refused.

Had this information been provided to the Federal Court during the Sea Hunt case, the Sea Hunt court would have called for an evidentiary hearing resulting in a dismissal of Sea Hunt’s claim. It should be noted that Sea Hunt’s locations for La Galga and the Juno are not included in AWOIS today.

The possibility that those two chests that washed off the raft in 1750 most likely were the personal property of Captain Huony.

The treasures of Assateague

Years after the wreck, he gave another account of the fleet’s loss. In 1771, Danial Huony willed his nephew, George Lysaght, his “fortune,” which consisted of “furniture, clothing, papers and correspondence, precious objects, and money.” He did not mention his later lament “…to crown my misfortune I find fourteen years in arrears of my salary earned with sweat and blood is forever lost without the hope of recovering any part of it which is a fatal stroke to me in a season where I consider myself unfit to return to labour anew for my bread; but necessity has no law.” This was provided to me by Liam Begley, a direct descendent of George Lysaght, Capt. Huony’s nephew and sole heir. Those chests most likely contain thousands of gold and silver coins and other valuable personal things that belonged to Captain Huony.

As recently as 2020, I asked the USFWS for permission to allow my archaeologists to perform non-intrusive magnetometer surveys in the area I pinpointed for them. They refused again, saying I must get permission from Spain, that they would not help me get the permission they wanted, and I must recognize that Spain owns the wreck. The historical record contradicts Spain’s control over Assateague Island. For now, the mystery of what’s in those two chests is being kept secret by the federal government.

The Treaty of Friendship of 1763

“The Owner of the Land Owns La Galga”

The Spaniards remained on Assateague for three days waiting to be ferried to the mainland. The Spaniards attempted no salvage as the locals descended on the wreck after the first day. Captain Huony first considered burning the wreck to keep the wreck out of the hands of the English. But Huony believed that might enrage the locals, so he declared that the “Owner of the Land” owned the wreck. His actions were reviewed in his court martial back in Spain, but he was absolved of any wrongdoing. Captain Huony had abandoned La Galga as the sand was piling up around the hull.

Fort San Marcos at St. Augustine was surrendered to Great Britain in 1763 along with La Galga buried under Assateague Island. Photo by the author aboard Santa Rosalia

In 1763, Spain signed a treaty with Great Britain ending the Seven Years War giving Great Britain everything on the North American continent, which included, for example, the fort at St. Augustine, Assateague Island, and La Galga. Great Btitain reciprocated and returned Cuba to Spain. Great Britain then surrendered La Galga to the United States in 1783 after the Revolution was over. Great Britain affirmed this interpretation in the Sea Hunt litigation,[p. 15] Because of this Treaty, I could not acknowledge Spain’s current claim of ownership as suggested by the federal government as Spain’s ownership had been expressly signed over to Great Britain in 1763. The 4th Circuit Court of Appeals reviewed this Treaty of 1763 in 2000 for applicability in this situation. No one told the Court that the wreck was not in the ocean. The basis for the 4th Circuit award was the misunderstood location of the shipwreck, and the Treaty was misapplied. The Court’s admiralty jurisdiction did not cover property on land. That land is owned by the Department of Interior today.

In 1943, the Department of Interior obtained the Virginia portion of Assateague through a condemnation proceeding. The court ordered that all fixtures on Assateague conveyed with the land. Spain’s attorney has stated that the 1763 Treaty only applied to moveable property not fixtures attached to the land[p. 15]. He just needs to be informed by the Department of Interior that the wreck is buried on Assateague Island and is excluded by the 1763 Treaty. In 1987, the Abandoned Shipwreck Act was passed which stated that shipwrecks buried on federal land belong to the federal government AND the public is to be informed of it. Currently the Department of Interior refuses to assert the rights of the United States in the shipwreck of La Galga and they refuse to inform the public of that fact.

In spite of all the law in this situation, the Department of Interior insists that I contact Spain directly for permission before my archaeologists can even run a metal detector over the site. Past attempts at dialogue have failed. It appears that the government is using Spain to shield themselves from their mistakes in the Sea Hunt litigation. But there are more mistakes recently uncovered that should render the entire proceeding void.

Spain was awarded, in error, the American bark, Sunbeam, which ran ashore in 1852. Spain never acquired legal standing to litigate rights to La Galga. The Department of Interior and the Kingdom of Spain are now free to conduct on their own the surveys now that I told them where to look. I have offered to conduct the verifications on Assateague for free. The responsibility now rests with them to comply with all historic preservation laws that have been intentionally ignored for the past fifteen years. (Another calculation says thirty-eight)

The Museum

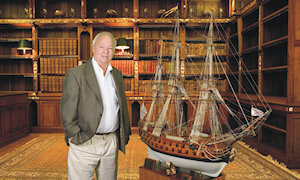

History and objects of historical interest belong in museums for the enjoyment and education of the people in the present. There are may shipwreck and maritime museums around the world. In 2007, I published The Hidden Galleon dedicated toward the goal of La Galga being excavated and her remains  being displayed in a museum as it deserves. In 1865, the steamboat, Bertrand, sank in the Missouri River. In 1968, the Bertrand was discovered by treasure hunters buried in a cornfield in the Desoto National Wildlife Refuge. The shipwreck was excavated and the artifacts were preserved and put on display. Hundreds of thousands come to the museum each year. As for La Galga, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has taken extraordinary steps to not only block archaeological investigations, but to keep the public from knowing about it. But, someday the shipwreck will be excavated and a museum built. When that happens, the model of La Galga, (right) will be donated and placed on permanent display. The model was completed in 2009 by Wilson (Bill) Bane.

being displayed in a museum as it deserves. In 1865, the steamboat, Bertrand, sank in the Missouri River. In 1968, the Bertrand was discovered by treasure hunters buried in a cornfield in the Desoto National Wildlife Refuge. The shipwreck was excavated and the artifacts were preserved and put on display. Hundreds of thousands come to the museum each year. As for La Galga, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has taken extraordinary steps to not only block archaeological investigations, but to keep the public from knowing about it. But, someday the shipwreck will be excavated and a museum built. When that happens, the model of La Galga, (right) will be donated and placed on permanent display. The model was completed in 2009 by Wilson (Bill) Bane.

And there’s more!

My involvement with the 1750 fleet doesn’t end here.

Three other ships of the fleet were lost on the coast of North Carolina. Cape Lookout contains the remains of two of the 1750 fleet and possibly a fortune in Spanish treasure! And the most significant of them all, was another ship under La Galga’s protection called the Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe carrying a cargo worth over a million dollars that entered Ocracoke Inlet in a shattered state. The captain, in desperation, offloaded his treasure onto two English sloops. What happened next would inspire one of the greatest adventure stories of all time—Treasure Island!

A Footnote

The timing of the loss of the 1750 fleet was dictated by the delays met by La Galga in Havana as she searched for crew and loaded cargo. Had the fleet left a day earlier or a day later, the outcome would certainly have been different. Two children’s classics in literature are tied to the fate of La Galga and the 1750 fleet.